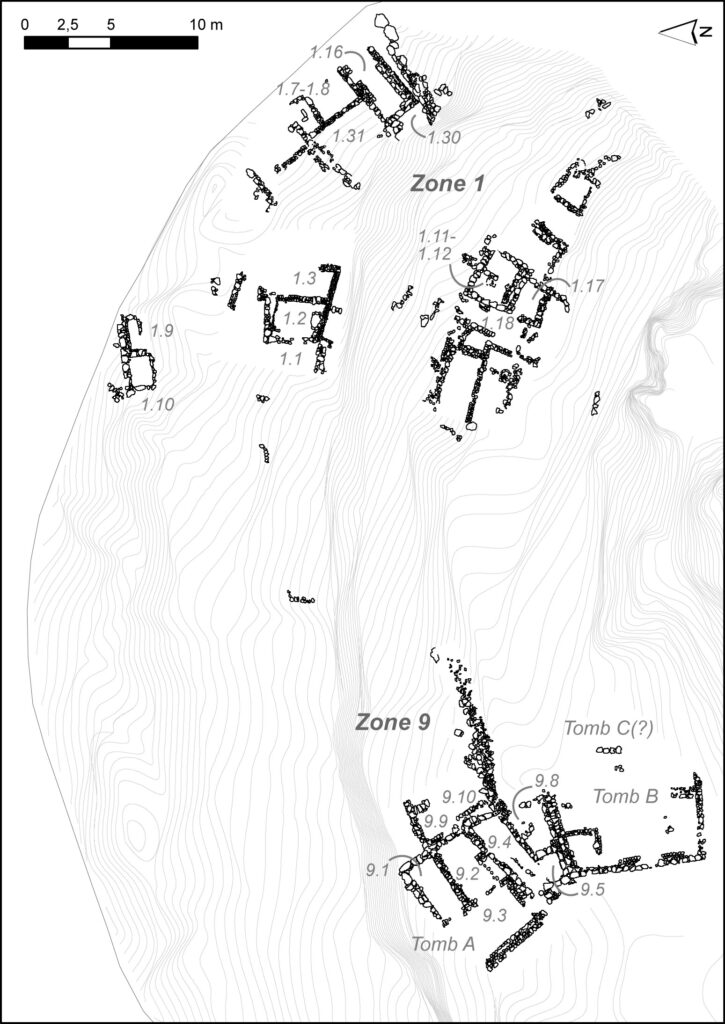

Even before excavation began, weathered human bones were observed on the seaward downhill terraces, revealing the presence of a cemetery. Excavations were directed by Ilse Schoep between 2007 and 2011 in zones 1 and 9, and by Aurore Schmitt in zone 9 from 2016 to 2019. A total of 30 rectangular compartments were identified (Fig. 1). Overlooking the sea, these structures form a cemetery composed of small, rectangular burial constructions, commonly referred to in the literature as house tombs. During the Prepalatial and early Protopalatial periods, house tombs were predominantly found in the northern and eastern regions of Crete, contrasting with tholos tombs, which were mostly (though not exclusively) concentrated in the south-central part of the island. From west to east, rectangular tombs have been excavated at sites such as Archanes, Malia, Istro, Gournia, Vasiliki, Linares, Petras, Palaikastro, and Zakros. Some burial sites consist of only one or two structures, but house tombs are more frequently found in small or larger clusters. At Sissi, the tombs were constructed in an agglutinative manner, with new compartments gradually added to existing ones – making it sometimes challenging to determine whether adjacent compartments should be considered part of the same tomb.

Most of the rectangular compartments excavated to date are located on two natural terraces on the northeast slope of the hill (zone 1). However, two (or possibly three) large tombs were also discovered on a rocky promontory approximately 30 meters further west (zone 9), just east of a World War II gun post. This suggests that the entire upper terrace between zone 1 and zone 9 may have been covered with burial structures, in which case the cemetery extended over an area of at least 1650 m². Additionally, poorly preserved wall remains on the lower terrace indicate the possible existence of more tombs closer to the sea and west of Compartments 1.1 and 1.9-1.10. Zone 9 is better protected from the elements compared to the northeast slope of the hill, where the north and east sectors of the upper terrace and the central and west sector of the lower terrace have been almost completely eroded down to bedrock. Besides zone 9, the best-preserved structures excavated so far are Compartments 1.2, 1.9-1.10, 1.16, 1.11-1.12, and 1.17. Excavation has only begun west of the open space 1.18, but the deposits there appear thick enough to be promising.

Zone 1

In zone 1, the tombs align with the orientation of the natural terraces. The rectangular compartments are small in size, with the largest measuring ca. 3.4 m by 1.6-2.7 m and the smallest barely covering 1 m². The walls were built using rubble masonry, with small and medium-sized fieldstones arranged on one or two faces, sometimes in association with a few larger blocks. Limestone is the most common building material, but sideropetra and sandstone were occasionally used as well. The builders often took advantage of the local topography by incorporating the irregularities of the bedrock in the construction. It is likely that the preserved walls simply served as the basis for superstructures made of perishable material, as suggested for instance by small fragments of burnt mudbrick recovered from Compartment 1.11 and the open space 1.30. Additionally, micromorphological analysis suggests that at least some of the walls could have been plastered. Floors varied across compartments: the natural bedrock was used in some of them, while a leveling layer of soil (often mixed with sherds or small stones) or a pebble floor was laid out in others. As is often the case in house tombs, the walls generally show no evidence of doorways, implying that the compartments were likely accessed from above – either through the roof or via an opening higher up in the wall. However, there are exceptions: an opening exists in the partition wall between Compartments 1.11 and 1.12, and two thresholds in the west and east walls of Compartment 1.7 indicate that the latter communicated with both Compartments 1.8 and 1.16.

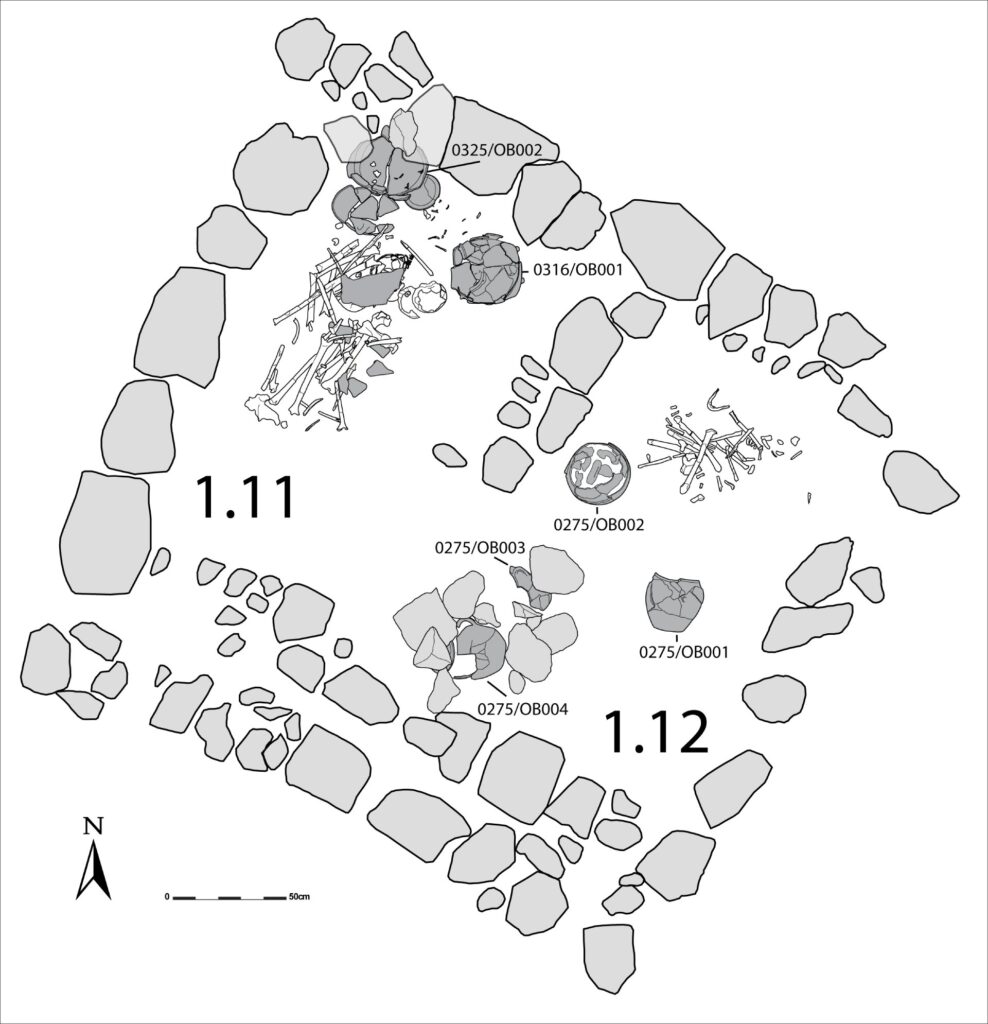

Current ceramic evidence from zone 1 spans the Early Minoan (EM) IIA (ca. 2650 BC) to Middle Minoan (MM) IIB (ca. 1750 BC) periods. The EM II burial deposits uncovered so far are concentrated on the upper terrace of the northeast slope of the hill, where excavations revealed the remains of an EM IIA-B house tomb consisting of at least three compartments (1.11, 1.12, and 1.17). This structure apparently collapsed, sealing the EM II burials, before being rebuilt during the MM IA period with a slightly different alignment. In Compartment 1.17, the EM II layer contained a collective primary burial deposit, whereas in Compartment 1.12, the primary burial of an adult male was uncovered alongside four jars containing the remains of perinatal individuals or infants (Fig. 2). Compartment 1.11 yielded two additional perinatal burials in clay containers, as well as a disturbed collective deposit with skeletal remains from a minimum of four individuals (three adults and one adolescent). It appears that Compartment 1.11 was used repeatedly for primary burials, leading to the disturbance of earlier remains. Some bones from the initial interments were removed and deposited elsewhere, and three of the skulls were found clustered in the northwest corner of the room. The bones of one individual were distributed in a manner suggesting that the corpse decomposed in a perishable rectangular container. The latter was closed by a terracotta lid, fragments of which were found above the skeletal remains. There is limited evidence of activity in zone 1 during the EM III period, except for a burial structure beneath the later

Compartment 1.2 and a primary burial associated with an EM III cup in Compartment 1.6. Additionally, a ritual deposit comprising a triton shell, a teapot, and two cups was discovered on a pebble floor under overhanging bedrock to the south of Compartments 1.2-1.3 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Ritual deposit to the south of Compartments 1.2-1.3 (© Sissi Project).

In contrast, MM IA – i.e. the last phase of the Prepalatial period – was a period of significant expansion in zone 1. Compartments 1.11-1.12 were rebuilt, and new burial structures were constructed on the lower terrace, including Compartments 1.9-1.10, Compartments 1.7-1.8-1.16, and possibly Compartments 1.2-1.3 (unless the latter dates back to EM III). Compartments 1.2, 1.7, 1.8 and 1.10 yielded the remains of disturbed primary burials. In contrast, Compartment 1.9 contained a large secondary deposit consisting of the bones of at least 13 individuals: nine adults, one adolescent, two children and one perinatal. These remains were carefully arranged by bone types, with long bones and skulls placed differently. However, the presence of some small bones suggests that certain body parts may have been transferred before full decomposition had occurred.

Compartment 1.16 stands apart in the context of the cemetery. It was constructed to the east of Compartments 1.7 and 1.31, partly on top of a large pottery deposit that had been placed under the overhanging bedrock. The particular deposit included cups, jugs, bowls, plates, dishes, as well as a broken (and empty) larnax. The good state of preservation of the vessels and the fact that some of them were stacked indicates that the deposit had been carefully placed rather than dumped. Compartment 1.16 (ca. 4.2 by 1.35 m in size) is one of the largest rooms in the cemetery. It was quite carefully built and provided with benches. It yielded pottery but only few bones, suggesting that it was perhaps not used for burials. It is only after the tomb collapsed, during the MM IIA period, that a large secondary deposit of pottery, stones, human and animal bones, and fragments of mudbrick seems to have been dumped here.

Zone 9

Although several of the Prepalatial tombs in zone 1 continued to be used during the MM IB and MM IIA periods, the best-preserved Protopalatial burial deposits were discovered in zone 9. Indeed, excavations in the southwestern part of the cemetery revealed two main burial structures (Tombs A and B) and a potential third tomb (Tomb C) located to the east of Tomb B. Only Tomb A has been fully excavated, revealing eight compartments, two of which (9.3 and 9.9) contained no human bones. Compartment 9.1 yielded the remains of 13 individuals (including three perinates) distributed across three superimposed strata. Notably, the main burial stratum comprised five primary deposits (on the floor, in pits, or in pithoi), in addition to a probable secondary burial: selected bones belonging to a single individual were collected after decomposition and placed in a pit in the southwest corner of the room. Later, another shallow pit was dug along the northeast wall, a pebble surface was installed, and the body of Individual 2 was interred. The skeleton of Individual 2 was also interfered with, when a new earth floor was laid across the compartment.

Compartment 9.2 contained a series of superimposed burial strata and the remains of a minimum number of 20 individuals, including adults but also eight immatures. The compartment provided evidence of both primary burials and processes of reduction. Additionally, missing bones suggest that specific skeletal elements were intentionally collected and removed from the tomb after the decomposition of the bodies. Individual 7 was placed in a terracotta larnax, a fragment of which was later reused for the burial of Individual 2. Three individuals were found in positions indicating that their bodies decomposed in narrow perishable containers, such as baskets or pieces of textile. A golden earring was found on the skull of Individual 8 and a golden stud nearby – remarkable personal ornaments given the scarcity of grave goods at Sissi.

In the eastern part of 9.4, a deep pit dug in the older burial strata was filled with c. 30 successive perinate burials (twenty-two weeks of amenorrhea to two lunar months post-partum), as well as primary and secondary deposits of bones belonging to a minimum of nine adults. An MM IIB cup was also found in the pit.

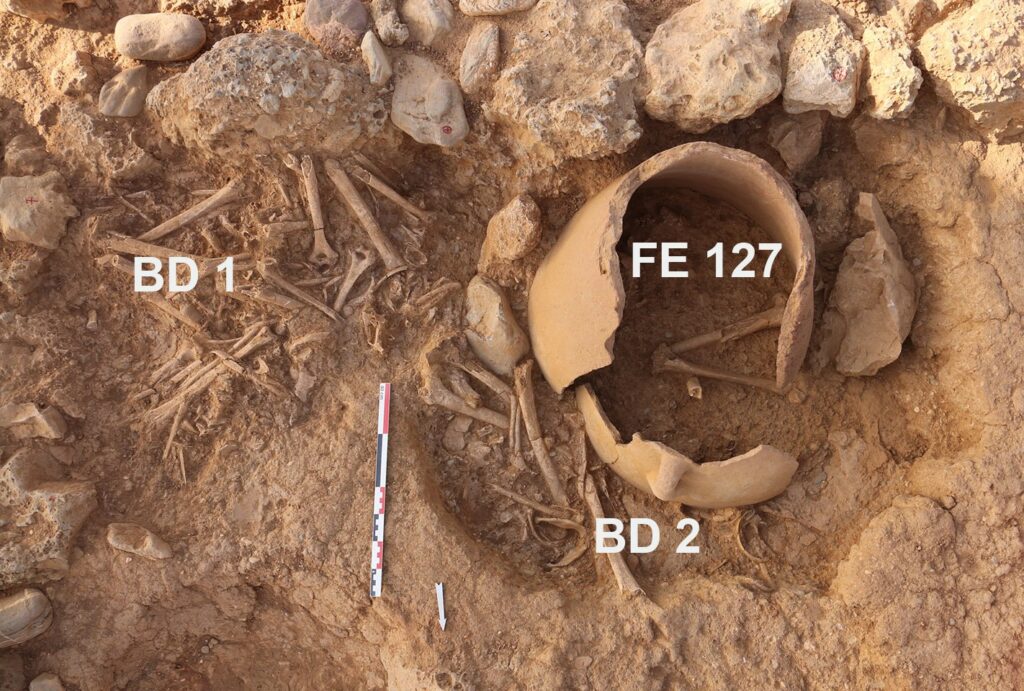

In Compartment 9.8, the initial depositions took place on a pebble floor (FE143). Most human bones were subsequently removed, leaving only residual remains in place, before an earthen floor (FE153) was laid out. Four pits were later dug into this floor to receive individual primary burial deposits, three of which were contained in fragmentary pithoi. Pithos FE127 was installed in a large pit, with a gap between the edge of the pit and the pithos filled with disarticulated bones (Fig. 4). This secondary bone deposit (labelled ‘Bone Deposit 2’), comprised approximately 140 bones from at least six incompletely represented individuals. Another secondary deposit (labelled ‘Bone Deposit 1’) occupied the southwest corner of the compartment. Stratigraphically at the same level as the primary burials, it consisted of 290 bones from at least nine individuals.

Fig. 4. Pithos burial FE127, Bone deposit 1 (BD1), Bone deposit 2 (BD2) in Compartment 9.8 (zone 9, Tomb A).

In Compartment 9.5, superimposed earth and pebble floors were identified, with vases (e.g. cups, lamp) placed on top of them, sometimes upside down. Two long bones were also identified on one of these floors.

Finally, to the east of Tomb A, space 9.10 yielded a secondary deposit of human bones placed on the bedrock.

Preliminary results

The built tombs of Sissi are as a rule poorly preserved and they yielded surprisingly few grave goods in comparison to the cemeteries of Mochlos and Archanes, for instance. Moreover, most of the pottery was found outside the tombs and therefore testify to ritual activities (rather than the deposition of grave goods). Nevertheless, the Sissi Archaeological Project has already significantly contributed towards a better understanding of Pre- and Protopalatial mortuary practices, mostly as a result of the involvement of archeo-anthropologists trained in archaeothanatology (also called field anthropology) since its inception. Until recently, excavation projects in Crete involved physical anthropologists only (if at all) in the study (rather than already in the excavation) of skeletal remains, with the consequence than meaningful information was lost about the exact position of osteological remains and hence the treatment of the body and its conditions of decomposition. In contrast, at Sissi, Dr. Isabelle Crevecoeur and Dr. Aurore Schmitt, both archaeo-anthropologists at the CNRS (France) are in charge of the excavation and documentation of mortuary deposits. Between 2007 and 2019, they thus recorded, in the field, unprecedented evidence about interment sequences and subsequent manipulations of human remains.

More specifically, the adoption of an archaeothanatological approach in the Sissi cemetery has led to two particularly significant observations. First, a substantial number of primary burials have been discovered, challenging the common interpretation of house tombs as ossuaries. Articulated bodies were deposited in the house tombs of Sissi and left to decompose in situ. It was only later, when new bodies were brought into the tombs, that earlier burial remains were sometimes disturbed, either accidentally or intentionally as part of a process known as ‘reduction’. These rearrangements of bones made for purely practical reasons related to space management must be distinguished from other types of secondary deposits, where partially or completely disarticulated skeletal elements are transferred from their original locus of decomposition to another one. In Sissi, such secondary deposits have been definitely identified in Compartments 1.9, 9.1 and space 9.10. The second major observation made by archaeothanatologists at Sissi concerns the treatment of subadults and especially perinatals. Until recently, young children were believed to be largely absent from house tombs. However, the evidence from Sissi suggests that the apparent scarcity of child burials in other cemeteries of rectangular tombs may be due not to the segregation of subadults in death, but to the small size and fragility of their bones, which may have been overlooked in early excavations that paid limited attention to skeletal remains.

Excavations in the Sissi cemetery have also provided new insights into the use of clay burial containers, which grew in importance at Sissi, as elsewhere in Crete, during the MM I period. At Sissi, pithoi and larnakes were exclusively used for primary burials. However, evidence suggests that they may have been reused for successive primary burials. In this way, it is possible (if not likely) that Bone Deposits 1 and 2 in Compartment 9.8 contain the disarticulated remains of individuals removed from the pithoi to make room for new, fresh corpses. Similarly, in space 1.29, most of the bones of previous burials were collected and rearranged outside the pithoi in preparation for the deposition of new bodies. The evidence from Sissi also illustrates that fragments of one or more pithoi could be used as burial containers in place of complete vessels.

Isotopic and DNA samples have also been collected and partly analyzed, the former by Argyro Nafplioti (British School at Athens) and the latter by Marie-France Deguilloux (Université de Bordeaux). Additionally, aDNA analyses are currently being carried out at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (Jena, Germany) as part of Philipp Stockhammer’s ERC project, titled MySocialBeIng. The results are expected to provide insights into the local or non-local origin of the community, as well as potential kingship ties (or the lack thereof) among the dead, thus contributing to a better understanding of the social organization at the site during the Pre- and Protopalatial periods.

Most of the tombs ceased to be used during the course of MM II. In zone 9, where a few burial deposits date to MM IIB, the remaining compartments were deliberately and ritually terminated before the beginning of MM IIIA – which is when the construction of the court-centered building started. The cemetery was then abandoned, not to be reused or reoccupied again.

Déderix S., Schmitt A., Crevecoeur I.

Bibliography

Crevecoeur, I. and Schmitt, A. 2009. Etude archéo-anthropologique de la nécropole (Zone 1). In: Driessen J. (dir.), Excavations at Sissi. Preliminary Report of the 2007-2008 Campaigns. Aegis 1. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, p. 45-56.

Crevecoeur, I., Schmitt, A. and Schoep, I. 2015. An Archaeothanatological Approach to the Study of Minoan Funerary Practices: Case-Studies from the Early and Middle Minoan Cemetery at Sissi, Crete. Journal of Field Archaeology 40(3), p. 283-299.

Crevecoeur, I., 2022. Excavation of a Pithos Burial in Compartment 1.23. Zone 1. In: Driessen J. (dir.) Excavations at Sissi V. Preliminary Report on the 2017-2019 Campaigns, Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, p. 55-57.

Déderix, S., Schmitt, A., Caloi, I. 2025. The death of collective tombs in Middle Bronze Age Crete: new evidence from Sissi. Antiquity 99(405), p. 727-745 [https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.3]

Deguilloux, M.-F., Pemonge, M.H., Schmitt, A., Driessen, J., Schoep, I., Carpentier, F., Crèvecour, I., 2022. Paleogenetic Analyses of Human Remains at Sissi. In: Driessen J. (dir.) Excavations at Sissi V. Preliminary Report on the 2017-2019 Campaigns, Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, p. 58-62.

Nafplioti, A., Driessen, J., Schmitt, A., Crevecoeur, I. 2021. Mobile lifeways: People at Pre- and Protopalatial Sissi (Crete). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 35 [https://doi.org/1016/j.jasrep.2020.102718]

Schmitt, A., Crevecoeur, I., Gilon, A. and Schoep, I., 2013. Apparition des inhumations individuelles en pithos à l’âge du Bronze en Crète : reflet d’une mutation sociale ? In : Transition, ruptures et continuité durant la Préhistoire. XXVIIe congrès préhistorique de France, Bordeaux-Les Eyzies, 2010. Volume 1. Paris : Société préhistorique française, p. 271-284.

Schmitt, A. and Sperandio, E. 2018. The Cemetery (Zone 9). Report on the 2016 Campaign. In: Driessen J. (dir.) Excavations at Sissi IV. Preliminary Report on the 2015-2016 Campaigns. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, p. 59-76.

Schmitt, A. and Déderix, S. 2021.Too many secondary burials. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 64 [10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101354]

Schmitt, A. and Déderix, S. 2022. The Prepalatial and Protopalatial Cemetery. In: Driessen J. (dir.), Excavations at Sissi V. Preliminary Report on the 2017-2019 Campaigns. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, p.37-54.

Schmitt, A. 2022. Defining collective burials: three case studies. In: Knüsel, C., Schotsmans, E., Castex, D. (dir), The Routledge Handbook of Archaeothanatology. Routledge, p. 207-222

Schoep, I. 2009. The excavation of the Cemetery (Zone 1). In: Driessen, J. (dir.) Excavations at Sissi. Preliminary Report of the 2007-2008 Campaigns. Aegis 1. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, p. 57-94.

Schoep, I., Schmitt, A. and Crevecoeur, I. 2011. The Cemetery at Sissi. In: Driessen, J. (dir.) Excavations at Sissi, II. Preliminary Report on the 2009-2010 Campaigns. Aegis 4. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, p. 41-67.

Schoep, I., Schmitt, A., Crevecoeur, I., and Déderix, S. 2012. The Cemetery at Sissi. In: Driessen, J. (dir.) Excavations at Sissi, III. Preliminary Report on the 2011 Campaign. Aegis 6. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, p. 27-51.

Schoep, I., Crevecoeur, I, Schmitt, A., Tomkins, P. 2017. Funerary practices at Sissi: The treatment of the body in the house tombs. In: Tsipopoulou, M. (dir.) Petras, Siteia – The Pre- and Proto- palatial cemetery in context, Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens 21, Aarhus University Press, p. 369-383.