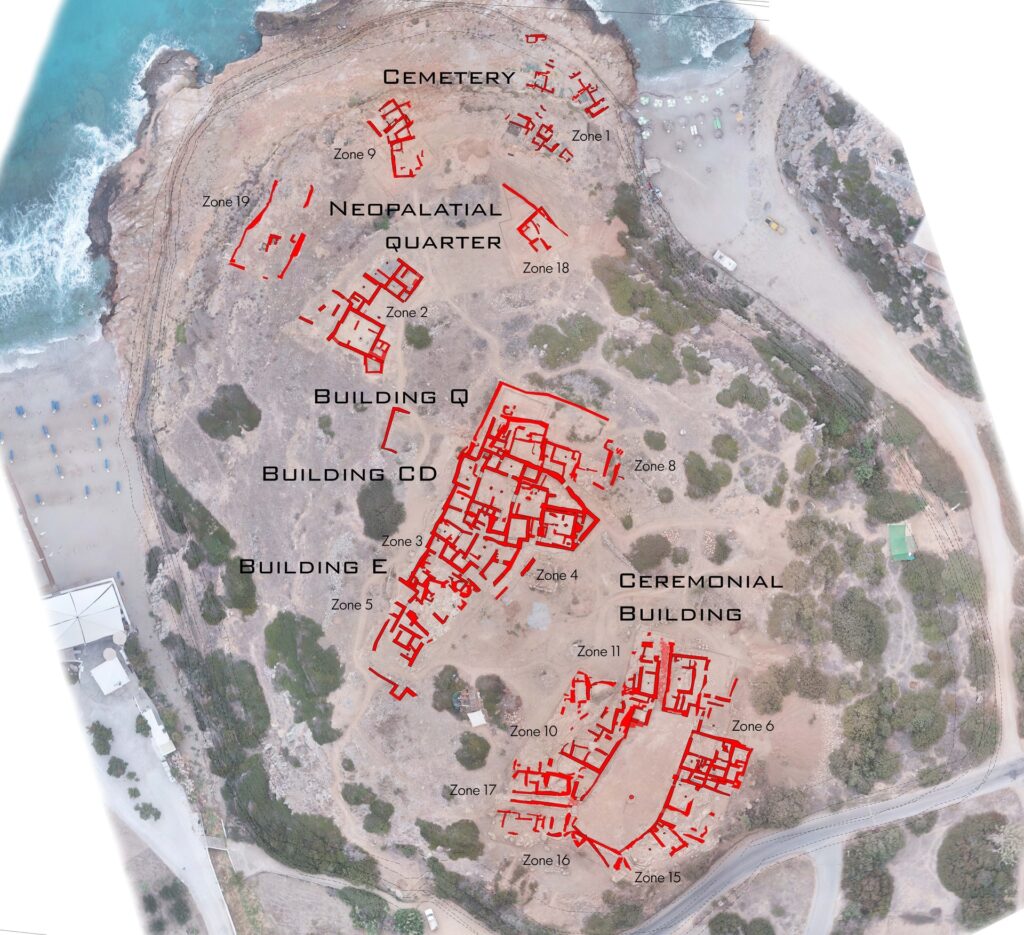

The Sissi Archaeological Project on the Kephali on Crete, represents one of the most important Bronze Age excavations in Crete during the past decade, because of its extent, chronological range and the type of buildings uncovered.

Less than 4 km east of the major palace centre at Malia sits the coastal hill of Kephali tou Agiou Antoniou, locally known as Buffo. With a beach on both sides, the hill lies at the outlet of the river flowing down the Selinari gorge, which is exactly opposite the Kephali.

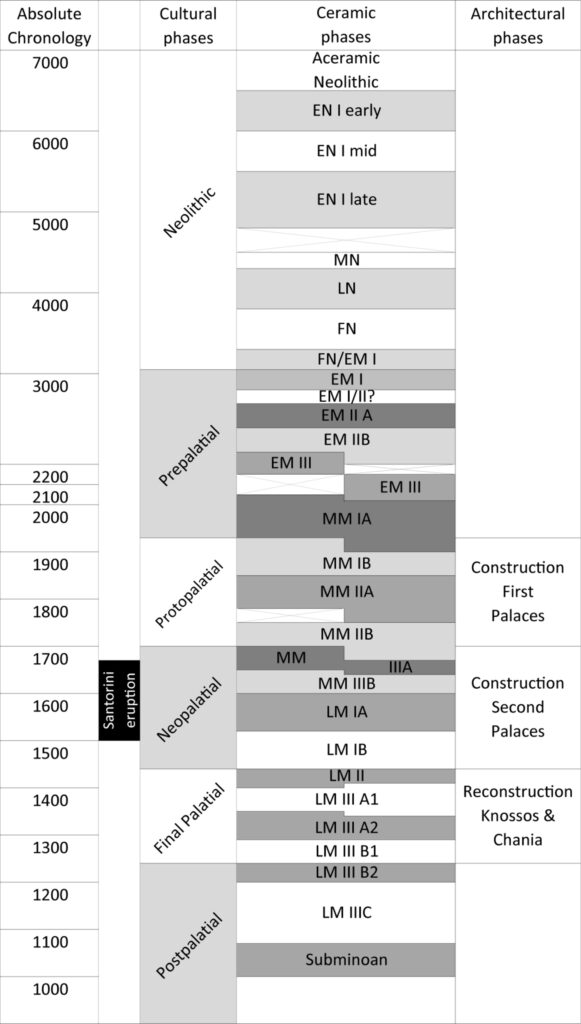

Then and now this gorge, together with the route north of the Anavlochos mountain, formed the only overland accesses from central to east Crete. This strategic position was undoubtedly the reason why the Kephali attracted the attention of early settlers and from its initial foundation around 2600 BCE (Early Minoan IIA), it remained occupied till the end of the Bronze Age, around 1200 BCE. During its early history, the Kephali was apparently only one out of a series of small hamlets, which dotted the coast of the larger Malia Bay but soon it would outgrow its neighbours and become the second settlement after Malia in the region.

The architectural remains of the Early and Middle Bronze Age (c. 2600-1700 BCE) are especially important in the area of the Court Building on the lower, south summit of the hill. The earliest remains are formed by two houses that were successively abandoned during EM IIA but one house was found with most of its objects in place. Lower down the slope, within the later Court Building, are important remains to the period immediately after, Early Minoan IIB. This building was destroyed by fire and incorporated into the later Neopalatial structure. On top of the hill, beneath Building CDE, are also isolated remains of this early period and of EM III/MM IA. Dating to this period, however, was also a cemetery of house-like tombs at the north foot of the hill, close to the sea. This allows us to follow the evolution of burial rites until the sudden abandonment of the cemetery in the 18th c. BCE, even if inhumation may have continued on the Middle Terrace, in Zone 18. The abandonment of the lower cemetery, however, may have coincided with the destruction of the First Palaces on the island, including the violent devastation of the nearby Malia Palace and Quartier Mu. Sissi too seems to have suffered by two successive earthquakes as shown by the remains found beneath the south wing of the Court Building.

In the following period, in Middle Minoan IIIA, around 1700 BCE, the settlement on the Kephali at Sissi seems to have steered a more independent course. The clearest indications for this are the construction of a fortification wall at the foot of the hill and especially the creation of a court-centred complex on a lower terrace of the summit, intentionally incorporating the earlier EM IIB and MM II remains in its construction. The central court, made of plaster and with a size of at least 450 m², could host larger crowds for festivals and religious meetings, as indicated by some ritual installations that were found. The complex suffered an earthquake destruction in Middle Minoan IIIA but was immediately afterwards reconstructed in Middle Minoan IIIB. At or around the time of the Santorini eruption, in Late Minoan IA, around 1525 BCE, however, this ceremonial complex was abandoned although settlement continued elsewhere on the Sissi hill. During this phase (MM IIIA-LM IB), the settlement covered most of the hill, including the middle terrace and the top.

Not long after, however, Sissi too, as so many other Minoan settlements and palace centres was destroyed by fire in Late Minoan IB (around 1450 BCE) and the nature of occupation drastically changes afterwards. On the summit of the hill, the ruins of one or more Neopalatial houses were partly incorporated and overbuilt by a new type of structure that betrays influences of the Mycenaean Mainland: a large complex organised around two columnar halls with central hearths. During its occupation, it suffered from an earthquake destruction accompanied by fire after which it needed rebuilding, and the south wing and some rooms in the north wing were abandoned. After a brief period of reoccupation, the north part was also abandoned late in the 13th c. BCE, when also the rest of the site was abandoned. Fortunately, apart from metal, many other objects were left in place, including a small snake-tube shrine between the two pillar halls. These finds allow a reconstruction of its internal functioning.

The Kephali hill would, in the centuries to follow, become a place of memory and gradually disappear from history until first tests by the local archaeological service in the 1960s by Kostis Davaras and then full-scale excavation from 2007 onwards by a team of the University of Louvain under the auspices of the Belgian School at Athens.

Jan Driessen