Summary

Excavated between 2007 and 2011, Building CD is one of the most impressive Postpalatial structures found on the island to date. It was erected on top of Buffo Hill, partly over Protopalatial and Neopalatial walls, and covers about 370 m², with more than 20 rooms. Its size, its distinctive architectural layout, and the archaeological material it produced, all point toward a major building with a specific role in the Late Minoan III local community.

During LM IIIB, Building CD was divided in three main sectors, respectively devoted to ritual, social gatherings/communal dinning, and artisanal activities. Two of these sectors were centred on a large hall with two vertical supports that opened, through a porch, onto the east and south “courts,” respectively. Apart from their monumental central room, these sectors comprise annexes mostly devoted to storage, small craft industry, and food processing. A small shrine containing snake tubes with horns of consecration, kalathoi, triton shells, a bench, and a possible altar, but no goddesses with upraised arms, was identified in the very core of the building. To the southwest of Building CD, a small square room opened only onto the south “court” and contained storage vessels, lithic tools related to grinding activities, and a very singular cooking feature and its associated refuse pit. The area also yielded a vast number of limpets and sea urchins, undoubtedly the remnants of a meal prepared in the room. This cook shed was most certainly used in close connection with the south court, where communal ceremonies and feasting activities may have taken place. The third sector, essentially consisting of service areas, was articulated around a central corridor and provided a spatial connection between the two less mundane parts of the building. It bore traces of various practices, such as storage in large containers, textile production, cooking, and food processing, as well as other domestic and artisanal activities.

An earthquake possibly explains the earlier LM IIIB destructions, but the reason for the final abandonment of Building CD in LM IIIB (advanced) has not been identified yet. Apart from metals, most rooms, however, were found with their artefacts, suggesting a planned abandonment of the building.

Detailed description

On the summit of the hill (21m asl), a large complex, Building CD, covering about 370 m² with more than 20 rooms was constructed during the Postpalatial period taking advantage of substantial Neopalatial remains and locally covering Protopalatial structures. At some point in its Postpalatial history, most certainly in an advanced stage of the LM IIIB phase, Building CD underwent important modifications. Many doorways were blocked and rooms sealed off (fig. 1).

What is really intriguing though is the care attested in some of the blockings: instead of the usual rubble roughly filling the openings, stones were carefully set, sometimes in courses, as if structural reinforcement was needed. This operation may have been related to earthquake damages, a hypothesis proposed by our colleagues Simon Jusseret and Charlotte Langohr[1]. The impact of this earthquake is particularly clear in the north and southwestern parts of the buildings where rooms were abandoned and yielded, together with other neighbouring areas, clear indications of seismic damage (such as large deposits of broken in situ vessels, stone heaps, as well as discarded repair and building materials). However, if an earthquake could possibly explain some LM IIIB modifications, the cause for the final abandonment of Building CD in LM IIIB (advanced) phase has not been identified yet.

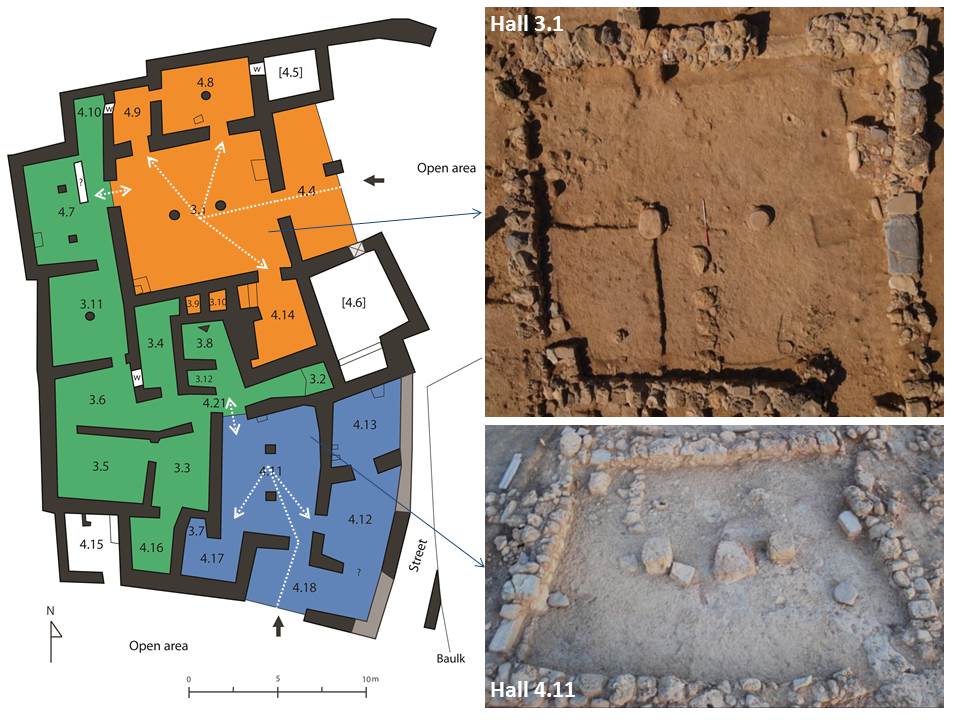

In its first phase, Building CD formed a large and impressive structure, especially by Postpalatial standards. It can be divided in three sectors (fig. 2).

The two main sectors, in orange and blue, were centred on a large hall with two vertical supports that opened, through a porch, onto the east and south courts respectively. Apart from their large central room that could accommodate substantial gatherings (at least 40 people for Room 3.1), these sectors comprised annexes mostly devoted to storage, small craft industry, and food processing. The third sector, in green, essentially consisting of service areas, was articulated around a central corridor and provided a spatial connection between the two less mundane parts of the building. It bore traces of various practices, such as storage in large containers, textile production, cooking, and food processing, as well as other domestic and artisanal activities. It also hosted a very peculiar room that we interpret as a shrine.

What is clear from the overall configuration of the building is that both halls were, potentially, quite readily accessible from the exterior. This impression of a tight connection between outside and inside is even reinforced in the case of Hall 3.1 with its monumental axial entrance. The visual permeability of both halls from the outside is also clearly worth noting. Visually and spatially, the third sector was clearly more remote from the exterior, especially where its southwest part is concerned. It is interesting to note that the relatively secluded character of spaces associated with weaving activities, particularly attested here in Room 3.6 by a large collection of spools, is a recurrent pattern in Minoan architecture, at least from the Neopalatial period onwards. In terms of spatial configuration, it is also clear that the third sector probably hosted most of the circulations within the building and clearly connected its different parts. It therefore appears that no efforts were made to provide direct access between the two main sectors but that communication had to pass through the service area. Jan Driessen[2] has argued that this configuration might actually be related to a gender differentiation. The potential evidence of what may have been wine production in Hall 3.1 together with the axiality and monumentality of the area suggested to him that it may have been a men’s hall. The presence of a hearth and three tripod cooking pots in Room 4.11 on the contrary may suggest that we are largely dealing with what are called maintenance activities in gender studies (which include cooking and food processing, textile production, domestic ware and tools management, maintenance of common spaces as well as caring and medical practices). Such activities are usually associated with women and give them an essential and quite powerful role within the community. This could then imply that 4.11 was the women’s hall. Interestingly, it is the latter hall which is closely connected to Room 3.8, located at the very core of the building (fig. 3). Within this room sits a triangular stone with a polished flat surface, carefully wedged into place by small stones set at its base. The specific inventory of artifacts – two tubular stands, six kalathoi, an inverted conical cup, imported transport vessels, two triton shells, water-worn pebbles, specialized ground stone assemblage – and the specific display of objects suggest that Room 3.8 represents a primary cult context[3].

The spatial arrangement of the objects around the triangular stone indicates that the latter was used as a place to display and deposit offerings or to pour libations. The other architectural features, such as stone with depressions and bench, suggest that Room 3.8 was specially designed to accommodate ritual activities connected to a cult and may therefore be called a shrine. It is worthy to note that not a single fragment of Figures with Upraised Arms, well attested in LM IIIC independent bench sanctuaries, was ever recovered at Sissi, suggesting that another kind of cult was performed in Shrine 3.8. This situation brings to mind the residential complex excavated in Quartier Nu at Malia, where Room X2 yielded a similar range of artifacts and presented a comparable architecture and location within the building. In both cases, the shrine was a small room located at the very core of the building and connected with gathering and artisanal areas, including the use of pumice in large quantities, possibly used as an abrasive powder in stone working activities[4]. Shrine 3.8 was still in use during the final phase of occupation of the building, a period which witnessed the abandonment of Room 4.15. Located in the southwest corner of the building, this small square room only opened on the south open area (fig. 4).

Apart from two painted-decorated small stirrup jars, a set of miniature vessels, a lentoid seal and a hut model, the room produced storage vessels (mostly pithoi), lithic tools related to grinding activities and a very singular cooking feature. This L-shaped stone structure was located in the northwest corner of the room and it partly limited a cooking area found full of ash, flecks of charcoal as well as seashells (limpets) and the remains of sea-urchins. It also produced a cooking plate, presumably in situ, made out of the footless base of a tripod cooking pot. The L-shaped feature and the cooking plate certainly worked together as a hearth, the wood being burnt in the area delimited by the small stretch of wall – where most of the ash was found – and the charcoal produced being used in connection with the cooking plate. Just to the west of this installation, a refuse pit in the form of a pithos embedded into the floor, was found. It was some 40cm deep and at its bottom, the bedrock seems to have been roughly cut. The pithos yielded a vast number of limpets and sea urchins, undoubtedly the remnants of a meal prepared in the room (fig. 5).

It therefore seems that this room may have worked simultaneously as a small storage space (pantry) and a kitchen. The fact that the room only opened onto the exterior suggests that it was used in close connection with the open area that was located immediately south of building CD. It can thus be argued that the meals prepared in the cooking area, the goods stored in the pithoi, and more generally the vessels and objects found in the room were used outside on specific occasions like communal ceremonies and feasting activities. That the south ‘court’ might have hosted such events is attested by three vast deposits of drinking vessels, one from the Neopalatial period[5], the second dated to LM IIIA, and the last one to LM IIIB middle. It is difficult to imagine that the secluded character of the kitchen-pantry 4.15 might have been dictated by the concern of keeping food and fire at some distance of other activities for reasons of cleanliness and safety because several other cooking areas are securely identified at different locations within Building CD. The existence, in LM III, of small rooms fitted with a hearth and yielding cooking wares and installations that were part of a building but only connected to the exterior – often in close relation with a relatively large open air space – is far from unusual. Examples can be found in Quartier Nu at Malia or in the so-called ‘cook sheds’ of the LM III town of Mochlos. The only thing that clearly distinguishes Room 4.15 from these humble ‘cook sheds’ or small kitchens-pantries is the fact that part of the material discovered in the room is of a type and quality (e.g. the decorated stirrup jars, the hut model, the miniature vessel set, the lentoid seal, etc.) which does not quite fit with the idea of a space only dedicated to food processing and short-term storage of consumable goods. One would then be tempted to suggest that Room 4.15 also acted as storeroom for less mundane objects that may have been used in relation with the activities taking place in the open area to the south. It was given up after the first phase, however.

Building CD was a large building complex with evidence for communal activities, especially suggested by the presence of the spacious and monumental Hall 3.1, clearly designed for the gathering of people. Public feasts may also have been performed in the south open-air area, directly connected to the kitchen-pantry 4.15. They may have been organised in relation with cultic activities in Room 3.8 and processions might have taken place. The variety and scale of artisanal activities performed in this building complex (stone working, weaving, wine/oil production) also deserve mention regarding its possible communal function.

[1] S. Jusseret, C. Langohr, M. Sintubin 2013. Tracking Earthquake Archaeological Evidence in Late Minoan IIIB (∼1300–1200 B.C.) Crete (Greece): A Proof of Concept, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 103: 6, 3026-3043. doi: 10.1785/0120130070.

[2] J. Driessen, Understanding Minoan in-house relationships on Late Bronze Age Crete, in Q. Letesson & C. Knappett (eds), Minoan Architecture and Urbanism: New Perspectives on an Ancient Built Environment, Oxford University Press, 2017.

[3] F. Gaignerot-Driessen, Goddesses Refusing to Appear? Reconsidering the Late Minoan III Figures with Upraised Arms, AJA 118.3 (2014). https://ajaonline.org/article/1818/

[4] F. Gaignerot-Driessen & J. Driessen, The presence of pumice in Late Minoan IIIB levels at Sissi, Crete, in Philistor. Studies in Honor of Costis Davaras (Prehistory Monographs 36), available at https://www.academia.edu/2491685/The_presence_of_Pumice_in_LM_IIIB_levels_at_Sissi_Crete

[5] F. Liard, in Sissi II, 197-210.

Quentin Letesson & Florence Driessen Gaignerot